Biophilia and Biophilic Design

- August 5th, 2021

- General

The term biophilia was coined by Erich Fromm, a social psychologist, in 1973 and is defined as “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive”.1 Biophilia was later used by Edward O. Wilson, a biologist, in 1984 as the inherent human tendency toward nature.2 Secondly, Clowney held an environmental philosophical point of view and defined biophilia as an environmental virtue that provides environmentalists with fruitful strategies and motivates them to flourish as human beings.3

Regenerating human energy by integrating nature into the built environment through biophilic design

So, biophilic design is the art of creating a connection between nature and the built environment to improve human wellbeing and the environment. To put it another way, biophilic design is a bridge between nature and the built environment to develop the built environment in harmony with nature. Therefore, the value of biophilic design has been well documented by studies showing the physiological and psychological benefits of reconnecting humans with nature.

Biophilic Design Applications

Additionally, biophilic design has three main applications: the direct experience of nature, the indirect experience of nature, and the experience of space and place.4 5 Thus, the implementation of these applications would be different depending on the project and its context.

So, the direct experience of nature refers to having direct contact with nature and natural processes, including, light, plants, water, animals, fire, etc. The indirect experience of nature refers to the exposure to natural representation and natural analogs, such as the image of nature, natural material, natural colour, biomimicry, etc. Moreover, the experience of space and place refers to spatial features and characteristics of the natural environment that have advanced human health and wellbeing. Further examples include prospect and refuge, organized complexity, mobility, navigating, and more.

Biophilic Design and Biophilic Urbanism

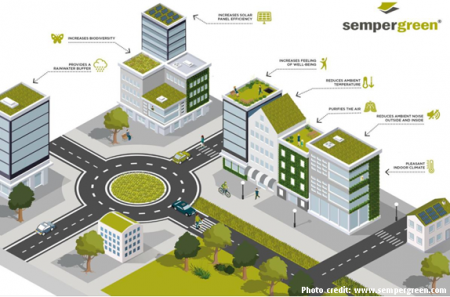

Biophilic design can be implemented on small scales such as the interior/exterior of a building, as well as on bigger scales like biophilic urbanism (Picture below). Further, studies have proven that biophilic design can improve mental and physical health, and environmental conditions, and provide economic benefits.

Biophilic design application and its benefits in a neighborhood scale

Depending on the context and the scope of the project, the importance or sequence of these benefits could vary, thus, the biophilic application and its different parameters have to be considered. In other words, different natural elements have different impacts on humans and the environment. For example, water features are mainly enhancing mental health while interior green walls or vertical gardens improve the air quality of the interior environment and have a great impact on human physical health.

Biophilic urbanism is more capable of optimizing the health of the city in different ways, such as improving the city environment, providing economic growth for the municipality through stormwater management, and improving the mental health of society.6 Researchers also indicate that the crime rate is significantly lower in neighbourhoods with more natural elements.7

Lastly, the most interesting fact about biophilic application is that the human brain can differentiate the difference between human-made nature and the natural environment. Therefore, biophilic designers should consider the point that the impact of nature’s direct experience on the human mind is not the same as the indirect experience and there are so many parameters that should be considered to create that impact.

Author: Asma Bashirivand

References:

[1] Fromm, E. (1973). The anatomy of human destructiveness. Greenwich, CT.[2] Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

[3] Clowney, D. (2013). Biophilia as an Environmental Virtue. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26(5), 999–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-013-9437-z

[4] Calabrese, E. F., & Dommert, A. (2018). Biophilia and the practice of Biophilic Design. Pathways to Well-Being in Design, 97–127. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351170048-6

[5] Kellert, S. R. and Calabrese E. F. (2018). Nature by design: The practice of biophilic design. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design, 1–214.

[6] McGee, B., & Marshall-Baker, A. (2015). Loving nature from the inside out: A biophilia matrix identification strategy for designers. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 8(4), 115– 130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715578644

[7] Clay, M., & Margalit, D. (2017). Seeking Parks, Plazas, and Spaces. Office Hours with a Geometric Group Theorist, 21–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vwmg8g.6